Player Basics

Introduction

In this section we'll focus on adding more functionality to the Player class. First we'll focus on the player's attack and the Projectile object. After that we'll focus on two of the main stats that the player will have: Boost and Cycle/Tick. And finally we'll start on the first piece of content that will be added to the game, which is different Player ships. From this section onward we'll also only focus on gameplay related stuff, while the previous 5 were mostly setup for everything.

Player Attack

The way the player will attack in this game is that each n seconds an attack will be triggered and executed automatically. In the end there will be 16 types of attacks, but pretty much all of them have to do with shooting projectiles in the direction that the player is facing. For instance, this one shoots homing projectiles:

![]media/(bytepath-6_1.gif)

While this one shoots projectiles at a faster rate but at somewhat random angles:

![]media/(bytepath-6_2.gif)

Attacks and projectiles will have all sorts of different properties and be affected by different things, but the core of it is always the same.

To achieve this we first need to make it so that the player attacks every n seconds. n is a number that will vary based on the attack, but the default one will be 0.24. Using the timer library that was explained in a previous section we can do this easily:

function Player:new()

...

self.timer:every(0.24, function()

self:shoot()

end)

end

With this we'll be calling a function called shoot every 0.24 seconds and inside that function we'll place the code that will actually create the projectile object.

So, now we can define what will happen in the shoot function. At first, for every shot fired we'll have a small effect to signify that a shot was fired. A good rule of thumb I have is that whenever an entity is created or deleted from the game, an accompanying effect should appear, as it masks the fact that an entity just appeared/disappeared out of nowhere on the screen and generally makes things feel better.

To create this new effect first we need to create a new game object called ShootEffect (you should know how to do this by now). This effect will simply be a square that lasts for a very small amount of time around the position where the projectile will be created from. The easiest way to get that going is something like this:

function Player:shoot()

self.area:addGameObject('ShootEffect', self.x + 1.2*self.w*math.cos(self.r),

self.y + 1.2*self.w*math.sin(self.r))

end

function ShootEffect:new(...)

...

self.w = 8

self.timer:tween(0.1, self, {w = 0}, 'in-out-cubic', function() self.dead = true end)

end

function ShootEffect:draw()

love.graphics.setColor(default_color)

love.graphics.rectangle('fill', self.x - self.w/2, self.y - self.w/2, self.w, self.w)

end

And that looks like this:

![]media/(bytepath-6_3.gif)

The effect code is rather straight forward. It's just a square of width 8 that lasts for 0.1 seconds, and this width is tweened down to 0 along that duration. One problem with the way things are now is that the effect's position is static and doesn't follow the player. It seems like a small detail because the duration of the effect is small, but try changing that to 0.5 seconds or something longer and you'll see what I mean.

One way to fix this is to pass the Player object as a reference to the ShootEffect object, and so in this way the ShootEffect object can have its position synced to the Player object:

function Player:shoot()

local d = 1.2*self.w

self.area:addGameObject('ShootEffect', self.x + d*math.cos(self.r),

self.y + d*math.sin(self.r), {player = self, d = d})

end

function ShootEffect:update(dt)

ShootEffect.super.update(self, dt)

if self.player then

self.x = self.player.x + self.d*math.cos(self.player.r)

self.y = self.player.y + self.d*math.sin(self.player.r)

end

end

function ShootEffect:draw()

pushRotate(self.x, self.y, self.player.r + math.pi/4)

love.graphics.setColor(default_color)

love.graphics.rectangle('fill', self.x - self.w/2, self.y - self.w/2, self.w, self.w)

love.graphics.pop()

end

The player attribute of the ShootEffect object is set to self in the player's shoot function via the opts table. This means that a reference to the Player object can be accessed via self.player in the ShootEffect object. Generally this is the way we'll pass references of objects from one another, because usually objects get created from within another objects function, which means that passing self achieves what we want. Additionally, we set the d attribute to the distance the effect should appear at from the center of the Player object. This is also done through the opts table.

Then in ShootEffect's update function we set its position to the player's. It's important to always check if the reference that will be accessed is actually set (if self.player then) because if it isn't than an error will happen. And often times, as we build more, it will be the case that entities will die while being referenced somewhere else and we'll try to access some of its values, but because it died, those values aren't set anymore and then an error is thrown. It's important to keep this in mind when referencing entities within each other like this.

Finally, the last detail is that I make it so that the square is synced with the player's angle, and then I also rotate that by 45 degrees to make it look cooler. The function used to achieve that was pushRotate and it looks like this:

function pushRotate(x, y, r)

love.graphics.push()

love.graphics.translate(x, y)

love.graphics.rotate(r or 0)

love.graphics.translate(-x, -y)

end

This is a simple function that pushes a transformation to the transformation stack. Essentially it will rotate everything by r around point x, y until we call love.graphics.pop. So in this example we have a square and we rotate around its center by the player's angle plus 45 degrees (pi/4 radians). For completion's sake, the other version of this function which also contains scaling looks like this:

function pushRotateScale(x, y, r, sx, sy)

love.graphics.push()

love.graphics.translate(x, y)

love.graphics.rotate(r or 0)

love.graphics.scale(sx or 1, sy or sx or 1)

love.graphics.translate(-x, -y)

end

These functions are pretty useful and will be used throughout the game so make sure you play around with them and understand them well!

Player Attack Exercises

80. Right now, we simply use an initial timer call in the player's constructor telling the shoot function to be called every 0.24 seconds. Assume an attribute self.attack_speed exists in the Player which changes to a random value between 1 and 2 every 5 seconds:

function Player:new(...)

...

self.attack_speed = 1

self.timer:every(5, function() self.attack_speed = random(1, 2) end)

self.timer:every(0.24, function() self:shoot() end)

How would you change the player object so that instead of shooting every 0.24 seconds, it shoots every 0.24/self.attack_speed seconds? Note that simply changing the value in the every call that calls the shoot function will not work.

81. In the last article we went over garbage collection and how forgotten references can be dangerous and cause leaks. In this article I explained how we will reference objects within one another using the Player and ShootEffect objects as examples. In this instance where the ShootEffect is a short-lived object that contains a reference to the Player inside it, do we need to care about dereferencing the Player reference so that it can be collected eventually or is it not necessary? In a more general way, when do we need to care about dereferencing objects that reference each other like this?

82. Using pushRotate, rotate the player around its center by 180 degrees. It should look like this:

![]media/(bytepath-6_4.gif)

83. Using pushRotate, rotate the line that points in the player's moving direction around its center by 90 degrees. It should look like this:

![]media/(bytepath-6_5.gif)

84. Using pushRotate, rotate the line that points in the player's moving direction around the player's center by 90 degrees. It should look like this:

![]media/(bytepath-6_6.gif)

85. Using pushRotate, rotate the ShootEffect object around the player's center by 90 degrees (on top of already rotating it by the player's direction). It should look like this:

![]media/(bytepath-6_7.gif)

Player Projectile

Now that we have the shooting effect done we can move on to the actual projectile. The projectile will have a movement mechanism that is very similar to the player's in that it's a physics object that has an angle and then we'll set its velocity according to that angle. So to start with, the call inside the shoot function:

function Player:shoot()

...

self.area:addGameObject('Projectile', self.x + 1.5*d*math.cos(self.r),

self.y + 1.5*d*math.sin(self.r), {r = self.r})

end

And this should have nothing unexpected. We use the same d variable that was defined earlier to set the Projectile's initial position, and then pass the player's angle as the r attribute. Note that unlike the ShootEffect object, the Projectile won't need anything more than the angle of the player when it was created, and so we don't need to pass the player in as a reference.

Now for the Projectile's constructor. The Projectile object will also have a circle collider (like the Player), a velocity and a direction its moving along:

function Projectile:new(area, x, y, opts)

Projectile.super.new(self, area, x, y, opts)

self.s = opts.s or 2.5

self.v = opts.v or 200

self.collider = self.area.world:newCircleCollider(self.x, self.y, self.s)

self.collider:setObject(self)

self.collider:setLinearVelocity(self.v*math.cos(self.r), self.v*math.sin(self.r))

end

The s attribute represents the radius of the collider, it isn't r because that one already is used for the movement angle. In general I'll use variables w, h, r or s to represent object sizes. The first two when the object is a rectangle, and the other two when it's a circle. In cases where the r variable is already being used for a direction (like in this one), then s will be used for the radius. Those attributes are also mostly for visual purposes, since most of the time those objects already have the collider doing all collision related work.

Another thing we do here, which I think I already explained in another article, is the opts.attribute or default_value construct. Because of the way or works in Lua, we can use this construct as a fast way of saying this:

if opts.attribute then

self.attribute = opts.attribute

else

self.attribute = default_value

end

We're checking to see if the attribute exists, and then setting some variable to that attribute, and if it doesn't then we set it to a default value. In the case of self.s, it will be set to opts.s if it was defined, otherwise it will be set to 2.5. The same applies to self.v. Finally, we set the projectile's velocity by using setLinearVelocity with the initial velocity of the projectile and the angle passed in from the Player. This uses the same idea that the Player uses for movement so that should be already understood.

If we now update and draw the projectile like:

function Projectile:update(dt)

Projectile.super.update(self, dt)

self.collider:setLinearVelocity(self.v*math.cos(self.r), self.v*math.sin(self.r))

end

function Projectile:draw()

love.graphics.setColor(default_color)

love.graphics.circle('line', self.x, self.y, self.s)

end

And that should look like this:

![]media/(bytepath-6_8.gif)

Player Projectile Exercises

86. From the player's shoot function, change the size/radius of the created projectiles to 5 and their velocity to 150.

87. Change the shoot function to spawn 3 projectiles instead of 1, while 2 of those projectiles are spawned with angles pointing to the player's angle +-30 degrees. It should look like this:

![]media/(bytepath-6_9.gif)

88. Change the shoot function to spawn 3 projectiles instead of 1, with the spawning position of each side projectile being offset from the center one by 8 pixels. It should look like this:

89. Change the initial projectile speed to 100 and make it accelerate up to 400 over 0.5 seconds after its creation.

Player & Projectile Death

Now that the Player can move around and attack in a basic way, we can start worrying about some additional rules of the game. One of those rules is that if the Player hits the edge of the play area, he will die. The same should be the case for Projectiles, since right now they are being spawned but they never really die, and at some point there will be so many of them alive that the game will slow down considerably.

So let's start with the Projectile object:

function Projectile:update(dt)

...

if self.x < 0 then self:die() end

if self.y < 0 then self:die() end

if self.x > gw then self:die() end

if self.y > gh then self:die() end

end

We know that the center of the play area is located at gw/2, gh/2, which means that the top-left corner is at 0, 0 and the bottom-right corner is at gw, gh. And so all we have to do is add a few conditionals to the update function of a projectile checking to see if its position is beyond any of those edges, and if it is, we call the die function.

The same logic applies for the Player object:

function Player:update(dt)

...

if self.x < 0 then self:die() end

if self.y < 0 then self:die() end

if self.x > gw then self:die() end

if self.y > gh then self:die() end

end

Now for the die function. This function is very simple and essentially what it will do it set the dead attribute to true for the entity and then spawn some visual effects. For the projectile the effect spawned will be called ProjectileDeathEffect, and like the ShootEffect, it'll be a square that lasts for a small amount of time and then disappears, although with a few differences. The main difference is that ProjectileDeathEffect will flash for a while before turning to its normal color and then disappearing. This gives a subtle but nice popping effect that looks good in my opinion. So the constructor could look like this:

function ProjectileDeathEffect:new(area, x, y, opts)

ProjectileDeathEffect.super.new(self, area, x, y, opts)

self.first = true

self.timer:after(0.1, function()

self.first = false

self.second = true

self.timer:after(0.15, function()

self.second = false

self.dead = true

end)

end)

end

We defined two attributes, first and second, which will denote in which stage the effect is in. If in the first stage, then its color will be white, while in the second its color will be what its color should be. After the second stage is done then the effect will die, which is done by setting dead to true. This all happens in a span of 0.25 seconds (0.1 + 0.15) so it's a very short lived and quick effect. Now for how the effect should be drawn, which is very similar to how ShootEffect was drawn:

function ProjectileDeathEffect:draw()

if self.first then love.graphics.setColor(default_color)

elseif self.second then love.graphics.setColor(self.color) end

love.graphics.rectangle('fill', self.x - self.w/2, self.y - self.w/2, self.w, self.w)

end

Here we simply set the color according to the stage, as I explained, and then we draw a rectangle of that color. To create this effect, we do it from the die function in the Projectile object:

function Projectile:die()

self.dead = true

self.area:addGameObject('ProjectileDeathEffect', self.x, self.y,

{color = hp_color, w = 3*self.s})

end

One of the things I failed to mention before is that the game will have a finite amount of colors. I'm not an artist and I don't wanna spend much time thinking about colors, so I just picked a few of them that go well together and used them everywhere. Those colors are defined in globals.lua and look like this:

default_color = {222, 222, 222}

background_color = {16, 16, 16}

ammo_color = {123, 200, 164}

boost_color = {76, 195, 217}

hp_color = {241, 103, 69}

skill_point_color = {255, 198, 93}

For the projectile death effect I'm using hp_color (red) to show what the effect looks like, but the proper way to do this in the future will be to use the color of the projectile object. Different attack types will have different colors and so the death effect will similarly have different colors based on the attack. In any case, the way the effect looks like is this:

Now for the Player death effect. The first thing we can do is mirror the Projectile die function and set dead to true when the Player reaches the edges of the screen. After that is done we can do some visual effects for it. The main visual effect for the Player death will be a bunch of particles that appear called ExplodeParticle, kinda like an explosion but not really. In general the particles will be lines that move towards a random angle from their initial position and slowly decrease in length. A way to get this working would be something like this:

function ExplodeParticle:new(area, x, y, opts)

ExplodeParticle.super.new(self, area, x, y, opts)

self.color = opts.color or default_color

self.r = random(0, 2*math.pi)

self.s = opts.s or random(2, 3)

self.v = opts.v or random(75, 150)

self.line_width = 2

self.timer:tween(opts.d or random(0.3, 0.5), self, {s = 0, v = 0, line_width = 0},

'linear', function() self.dead = true end)

end

Here we define a few attributes, most of them are self explanatory. The additional thing we do is that over a span of between 0.3 and 0.5 seconds, we tween the size, velocity and line width of the particle to 0, and after that tween is done, the particle dies. The movement code for particle is similar to the Projectile, as well as the Player, so I'm going to skip it. It simply follows the angle using its velocity.

And finally the particle is drawn as a line:

function ExplodeParticle:draw()

pushRotate(self.x, self.y, self.r)

love.graphics.setLineWidth(self.line_width)

love.graphics.setColor(self.color)

love.graphics.line(self.x - self.s, self.y, self.x + self.s, self.y)

love.graphics.setColor(255, 255, 255)

love.graphics.setLineWidth(1)

love.graphics.pop()

end

As a general rule, whenever you have to draw something that is going to be rotated (in this case by the angle of direction of the particle), draw is as if it were at angle 0 (pointing to the right). So, in this case, we have to draw the line from left to right, with the center being the position of rotation. So s is actually half the size of the line, instead of its full size. We also use love.graphics.setLineWidth so that the line is thicker at the start and then becomes skinnier as time goes on.

The way these particles are created is rather simple. Just create a random number of them on the die function:

function Player:die()

self.dead = true

for i = 1, love.math.random(8, 12) do

self.area:addGameObject('ExplodeParticle', self.x, self.y)

end

end

One last thing you can do is to bind a key to trigger the Player's die function, since the effect won't be able to be seen properly at the edge of the screen:

function Player:new(...)

...

input:bind('f4', function() self:die() end)

end

And all that looks like this:

This doesn't look very dramatic though. One way of really making something seem dramatic is by slowing time down a little. This is something a lot of people don't notice, but if you pay attention lots of games slow time down slightly whenever you get hit or whenever you die. A good example is Downwell, this video shows its gameplay and I marked the time when a hit happens so you can pay attention and see it for yourself.

Doing this ourselves is rather easy. First we can define a global variable called slow_amount in love.load and set it to 1 initially. This variable will be used to multiply the delta that we send to all our update functions. So whenever we want to slow time down by 50%, we set slow_amount to 0.5, for instance. Doing this multiplication can look like this:

function love.update(dt)

timer:update(dt*slow_amount)

camera:update(dt*slow_amount)

if current_room then current_room:update(dt*slow_amount) end

end

And then we need to define a function that will trigger this work. Generally we want the time slow to go back to normal after a small amount of time. So it makes sense that this function should have a duration attached to it, on top of how much the slow should be:

function slow(amount, duration)

slow_amount = amount

timer:tween('slow', duration, _G, {slow_amount = 1}, 'in-out-cubic')

end

And so calling slow(0.5, 1) means that the game will be slowed to 50% speed initially and then over 1 second it will go back to full speed. One important thing to note here that the 'slow' string is used in the tween function. As explained in an earlier article, this means that when the slow function is called when the tween of another slow function call is still operating, that other tween will be cancelled and the new tween will continue from there, preventing two tweens from operating on the same variable at the same time.

If we call slow(0.15, 1) when the player dies it looks like this:

Another thing we can do is add a screen shake to this. The camera module already has a :shake function to it, and so we can add the following:

function Player:die()

...

camera:shake(6, 60, 0.4)

...

end

And finally, another thing we can do is make the screen flash for a few frames. This is something else that lots of games do that you don't really notice, but it helps sell an effect really well. This is a rather simple effect: whenever we call flash(n), the screen will flash with the background color for n frames. One way we can do this is by defining a flash_frames global variable in love.load that starts as nil. Whenever flash_frames is nil it means that the effect isn't active, and whenever it's not nil it means it's active. The flash function looks like this:

function flash(frames)

flash_frames = frames

end

And then we can set this up in the love.draw function:

function love.draw()

if current_room then current_room:draw() end

if flash_frames then

flash_frames = flash_frames - 1

if flash_frames == -1 then flash_frames = nil end

end

if flash_frames then

love.graphics.setColor(background_color)

love.graphics.rectangle('fill', 0, 0, sx*gw, sy*gh)

love.graphics.setColor(255, 255, 255)

end

end

First, we decrease flash_frames by 1 every frame, and then if it reaches -1 we set it to nil because the effect is over. And then whenever the effect is not over, we simply draw a big rectangle covering the whole screen that is colored as background_color. Adding this to the die function like this:

function Player:die()

self.dead = true

flash(4)

camera:shake(6, 60, 0.4)

slow(0.15, 1)

for i = 1, love.math.random(8, 12) do

self.area:addGameObject('ExplodeParticle', self.x, self.y)

end

end

Gets us this:

Very subtle and barely noticeable, but it's small details like these that make things feel more impactful and nicer.

Player/Projectile Death Exercises

90. Without using the first and second attribute and only using a new current_color attribute, what is another way of achieving the changing colors of the ProjectileDeathEffect object?

91. Change the flash function to accept a duration in seconds instead of frames. Which one is better or is it just a matter of preference? Could the timer module use frames instead of seconds for its durations?

Player Tick

Now we'll move on to another crucial part of the Player which is its cycle mechanism. The way the game works is that in the passive skill tree there will be a bunch of skills you can buy that will have a chance to be triggered on each cycle. And a cycle is just a counter that is triggered every n seconds. We need to set this up in a basic way. And to do that we'll just make it so that the tick function is called every 5 seconds:

function Player:new(...)

...

self.timer:every(5, function() self:tick() end)

end

In the tick function, for now the only thing we'll do is add a little visual effect called TickEffect any time a tick happens. This effect is similar to the refresh effect in Downwell (see Downwell video I mentioned earlier in this article), in that it's a big rectangle over the Player that goes up a little. It looks like this:

The first thing to notice is that it's a big rectangle that covers the player and gets smaller over time. But also that, like the ShootEffect, it follows the player. Which means that we know we'll need to pass the Player object as a reference to the TickEffect object:

function Player:tick()

self.area:addGameObject('TickEffect', self.x, self.y, {parent = self})

end

function TickEffect:update(dt)

...

if self.parent then self.x, self.y = self.parent.x, self.parent.y end

end

Another thing we can see is that it's a rectangle that gets smaller over time, but only in height. An easy way to do that is like this:

function TickEffect:new(area, x, y, opts)

TickEffect.super.new(self, area, x, y, opts)

self.w, self.h = 48, 32

self.timer:tween(0.13, self, {h = 0}, 'in-out-cubic', function() self.dead = true end)

end

If you try this though, you'll see that the rectangle isn't going up like it should and it's just getting smaller around the middle of the player. One day to fix this is by introducing an y_offset attribute that gets bigger over time and that is subtracted from the y position of the TickEffect object:

function TickEffect:new(...)

...

self.y_offset = 0

self.timer:tween(0.13, self, {h = 0, y_offset = 32}, 'in-out-cubic',

function() self.dead = true end)

end

function TickEffect:update(dt)

...

if self.parent then self.x, self.y = self.parent.x, self.parent.y - self.y_offset end

end

And in this way we can get the desired effect. For now this is all that the tick function will do. Later as we add stats and passives it will have more stuff attached to it.

Player Boost

Another important piece of gameplay is the boost. Whenever the user presses up, the player should start moving faster. And whenever the user presses down, the player should start moving slower. This boost mechanic is a core part of the gameplay and like the tick, we'll focus on the basics of it now and later add more to it.

First, lets get the button pressing to work. One of the attributes we have in the player is max_v. This sets the maximum velocity with which the player can move. What we want to do whenever up/down is pressed is change this value so that it becomes higher/lower. The problem with doing this is that after the button is done being pressed we need to go back to the normal value. And so we need another variable to hold the base value and one to hold the current value.

Whenever there's a stat (like velocity) that needs to be changed in game by modifiers, this (needing a base value and a current one) is a very common pattern. Later on as we add more stats and passives into the game we'll go into this with more detail. But for now we'll add an attribute called base_max_v, which will contain the initial/base value of the maximum velocity, and the normal max_v attribute will hold the current maximum velocity, affected by all sorts of modifiers (like the boost).

function Player:new(...)

...

self.base_max_v = 100

self.max_v = self.base_max_v

end

function Player:update(dt)

...

self.max_v = self.base_max_v

if input:down('up') then self.max_v = 1.5*self.base_max_v end

if input:down('down') then self.max_v = 0.5*self.base_max_v end

end

With this, every frame we're setting max_v to base_max_v and then we're checking to see if the up or down buttons are pressed and changing max_v appropriately. It's important to notice that this means that the call to setLinearVelocity that uses max_v has to happen after this, otherwise it will all fall apart horribly!

Now that we have the basic boost functionality working, we can add some visuals. The way we'll do this is by adding trails to the player object. This is what they'll look like:

The creation of trails in general follow a pattern. And the way I do it is to create a new object every frame or so and then tween that object down over a certain duration. As the frames pass and you create object after object, they'll all be drawn near each other and the ones that were created earlier will start getting smaller while the ones just created will still be bigger, and the fact that they're all created from the bottom part of the player and the player is moving around, means that we'll get the desired trail effect.

To do this we can create a new object called TrailParticle, which will essentially just be a circle with a certain radius that gets tweened down along some duration:

function TrailParticle:new(area, x, y, opts)

TrailParticle.super.new(self, area, x, y, opts)

self.r = opts.r or random(4, 6)

self.timer:tween(opts.d or random(0.3, 0.5), self, {r = 0}, 'linear',

function() self.dead = true end)

end

Different tween modes like 'in-out-cubic' instead of 'linear', for instance, will make the trail have a different shape. I used the linear one because it looks the best to me, but your preference might vary. The draw function for this is just drawing a circle with the appropriate color and with the radius using the r attribute.

On the Player object's end, we can create new TrailParticles like this:

function Player:new(...)

...

self.trail_color = skill_point_color

self.timer:every(0.01, function()

self.area:addGameObject('TrailParticle',

self.x - self.w*math.cos(self.r), self.y - self.h*math.sin(self.r),

{parent = self, r = random(2, 4), d = random(0.15, 0.25), color = self.trail_color})

end)

And so every 0.01 seconds (this is every frame, essentially), we spawn a new TrailParticle object behind the player, with a random radius between 2 and 4, random duration between 0.15 and 0.25 seconds, and color being skill_point_color, which is yellow.

One additional thing we can do is changing the color of the particles to blue whenever up or down is being pressed. To do this we must add some logic to the boost code, namely, we need to be able to tell when a boost is happening, and to do this we'll add a boosting attribute. Via this attribute we'll be able to know when a boost is happening and then change the color being referenced in trail_color accordingly:

function Player:update(dt)

...

self.max_v = self.base_max_v

self.boosting = false

if input:down('up') then

self.boosting = true

self.max_v = 1.5*self.base_max_v

end

if input:down('down') then

self.boosting = true

self.max_v = 0.5*self.base_max_v

end

self.trail_color = skill_point_color

if self.boosting then self.trail_color = boost_color end

end

And so with this we get what we wanted by changing trail_color to boost_color (blue) whenever the player is being boosted.

Player Ship Visuals

Now for the last thing this article will cover: ships! The game will have various different ship types that the player can be, each with different stats, passives and visuals. Right now we'll focus only the visual part and we'll add 1 ship, and as an exercise you'll have to add 7 more.

One thing that I should mention now that will hold true for the entire tutorial is something regarding content. Whenever there's content to be added to the game, like various ships, or various passives, or various options in a menu, or building the skill tree visually, etc, you'll have to do most of that work yourself. In the tutorial I'll cover how to do it once, but when that's covered and it's only a matter of manually and mindlessly adding more of the same, it will be left as an exercise.

This is both because covering literally everything with all details would take a very long time and make the tutorial super big, and also because you need to learn if you actually like doing the manual work of adding content into the game. A big part of game development is just adding content and not doing anything "new", and depending on who you are personality wise you may not like the fact that there's a bunch of work to do that's just dumb work that might be not that interesting. In those cases you need to learn this sooner rather than later, because it's better to then focus on making games that don't require a lot of manual work to be done, for instance. This game is totally not that though. The skill tree will have about 800 nodes and all those have to be set manually (and you will have to do that yourself if you want to have a tree that big), so it's a good way to learn if you enjoy this type of work or not.

In any case, let's get started on one ship. This is what it looks like:

As you can see, it has 3 parts to it, one main body and two wings. The way we'll draw this is as a collection of simple polygons, and so we have to define 3 different polygons. We'll define the polygon's positions as if it is turned to the right (0 angle, as I explained previously). It will be something like this:

function Player:new(...)

...

self.ship = 'Fighter'

self.polygons = {}

if self.ship == 'Fighter' then

self.polygons[1] = {

...

}

self.polygons[2] = {

...

}

self.polygons[3] = {

...

}

end

end

And so inside each polygon table, we'll define the vertices of the polygon. To draw these polygons we'll have to do some work. First, we need to rotate the polygons around the player's center:

function Player:draw()

pushRotate(self.x, self.y, self.r)

love.graphics.setColor(default_color)

-- draw polygons here

love.graphics.pop()

end

After this, we need to go over each polygon:

function Player:draw()

pushRotate(self.x, self.y, self.r)

love.graphics.setColor(default_color)

for _, polygon in ipairs(self.polygons) do

-- draw each polygon here

end

love.graphics.pop()

end

And then we draw each polygon:

function Player:draw()

pushRotate(self.x, self.y, self.r)

love.graphics.setColor(default_color)

for _, polygon in ipairs(self.polygons) do

local points = fn.map(polygon, function(k, v)

if k % 2 == 1 then

return self.x + v + random(-1, 1)

else

return self.y + v + random(-1, 1)

end

end)

love.graphics.polygon('line', points)

end

love.graphics.pop()

end

The first thing we do is getting all the points ordered properly. Each polygon will be defined in local terms, meaning, a distance from the center of that is assumed to be 0, 0. This means that each polygon does now not know at which position it is in the game world yet.

The fn.map function goes over each element in a table and applies a function to it. In this case the function is checking to see if the index of the element is odd or even, and if its odd then it means it's for the x component, and if its even then it means it's for the y component. And so in each of those cases we simply add the x or y position of the player to the vertex, as a well as a random number between -1 and 1, so that the ship looks a bit wobbly and cooler. Then, finally, love.graphics.polygon is called to draw all those points.

Now, here's what the definition of each polygon looks like:

self.polygons[1] = {

self.w, 0, -- 1

self.w/2, -self.w/2, -- 2

-self.w/2, -self.w/2, -- 3

-self.w, 0, -- 4

-self.w/2, self.w/2, -- 5

self.w/2, self.w/2, -- 6

}

self.polygons[2] = {

self.w/2, -self.w/2, -- 7

0, -self.w, -- 8

-self.w - self.w/2, -self.w, -- 9

-3*self.w/4, -self.w/4, -- 10

-self.w/2, -self.w/2, -- 11

}

self.polygons[3] = {

self.w/2, self.w/2, -- 12

-self.w/2, self.w/2, -- 13

-3*self.w/4, self.w/4, -- 14

-self.w - self.w/2, self.w, -- 15

0, self.w, -- 16

}

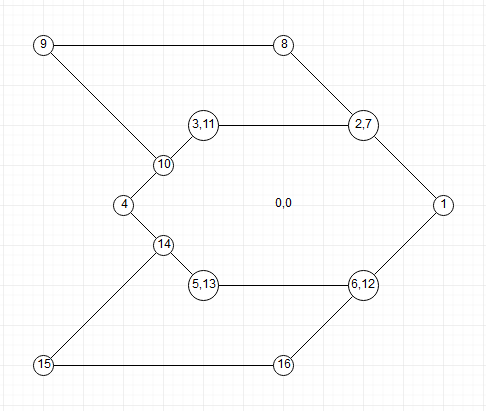

The first one is the main body, the second is the top wing and the third is the bottom wing. All vertices are defined in an anti-clockwise manner, and the first point of a line is always the x component, while the second is the y component. Here I'll show a drawing that maps each vertex to the numbers outlined to the side of each point pair above:

And as you can see, the first point is way to the right and vertically aligned with the center, so its self.w, 0. The next is a bit to the left and above the first, so its self.w/2, -self.w/2, and so on.

Finally, another thing we can do after adding this is making the trails match the ship. For this one, as you can see in the gif I linked before, it has two trails coming out of the back instead of just one:

function Player:new(...)

...

self.timer:every(0.01, function()

if self.ship == 'Fighter' then

self.area:addGameObject('TrailParticle',

self.x - 0.9*self.w*math.cos(self.r) + 0.2*self.w*math.cos(self.r - math.pi/2),

self.y - 0.9*self.w*math.sin(self.r) + 0.2*self.w*math.sin(self.r - math.pi/2),

{parent = self, r = random(2, 4), d = random(0.15, 0.25), color = self.trail_color})

self.area:addGameObject('TrailParticle',

self.x - 0.9*self.w*math.cos(self.r) + 0.2*self.w*math.cos(self.r + math.pi/2),

self.y - 0.9*self.w*math.sin(self.r) + 0.2*self.w*math.sin(self.r + math.pi/2),

{parent = self, r = random(2, 4), d = random(0.15, 0.25), color = self.trail_color})

end

end)

end

And here we use the technique of going from point to point based on an angle to get to our target. The target points we want are behind the player (0.9*self.w behind), but each offset by a small amount (0.2*self.w) along the opposite axis to the player's direction.

And all this looks like this:

Ship Visuals Exercises

As a small note, the (CONTENT) tag will mark exercises that are the content of the game itself. Exercises marked like this will have no answers and you're supposed to do them 100% yourself! From now on, more and more of the exercises will be like this, since we're starting to get into the game itself and a huge part of it is just manually adding content to it.

92. (CONTENT) Add 7 more ship types. To add a new ship type, simply add another conditional elseif self.ship == 'ShipName' then to both the polygon definition and the trail definition. Here's what the ships I made look like (but obviously feel free to be 100% creative and do your own designs):